- Home

- Shane McKenzie

Fairy

Fairy Read online

Cecilia will do anything to have a baby. Anything.

Cecilia has tried everything to have the one thing she wants most—a baby. She’s been through every procedure, taken every medication. Nothing seems to work. Her body simply refuses to grow the life she so desperately yearns for. Her jealousy is making her lash out at the pregnant women around her. She’s starting to worry about her sanity.

But all is not lost. There is still one way. And Cecilia will do whatever it takes.

Even if it means inviting an ancient creature into her bedroom.

Fairy

Shane McKenzie

Dedication

For my wife Melinda. I’ll be your fairy, baby.

An Introduction

By J. F. Gonzalez

It’s not often that I’m solicited for introductions or to write about a colleague.

The few times I’ve done it the writer in question is (a) dead, (b) a peer, colleague or friend, and, in one rare case, (c) somewhat of a legend in the field.

Thankfully, Shane McKenzie isn’t dead. And he isn’t a legend in the field of horror fiction yet. I do consider him a peer and a trusted colleague, though, and I’m sure if we lived closer, allowing us more social time, we’d probably be friends.

What Shane McKenzie is, however, is a new voice in the field of horror and suspense fiction, and one that I suspect will not fade away soon.

This will become apparent when you dip into the novella you hold in your hands. Despite the connotations of fantasy in the title, rest assured this tale is far from whatever preconceived notions that genre conjures.

No. Fairy is the stuff of nightmares.

Despite that, Fairy is still rooted in fantasy.

I realize that genre term means many things to people. For those who began reading genre fiction within the last ten years or so, the term probably conjures images of knights and unicorns and those cutesy fairies with the butterfly wings who zing about granting wishes or performing benevolent magic.

This story is far from that. The fantasy I’m referring to here is how the term was originally used in the SF/fantasy field (of which horror is a part).

You see, back in the Mesozoic Period (that is, 1950-1986 or so), the term fantasy was often used to label the works of authors normally thought of as horror writers.

Richard Matheson. Charles Beaumont. Robert Bloch. Charles L. Grant. Stephen King. At one time or another during this period, the fiction produced by these writers was labeled fantasy by writers, editors, publishers and booksellers. This term was used to differentiate their works from the science fiction genre. It gave the propeller heads fair warning—pick up a book with the fantasy label and you probably won’t get a tale set on another planet, or some space opera.

More often than not, you got a horror story.

I kid you not. I still recall reading stories labeled as fantasy as a kid and being blown away by them. They were clearly horror stories. I didn’t know what to make of the term. Charles L. Grant later coined the term dark fantasy to further differentiate tales of horror from the more sword-and-sorcery and general fantasy tales that were often lumped in under the fantasy banner. You see, back then, fantasy was an umbrella term to encompass everything from contemporary supernatural horror, Twilight Zone-type fantasy of the kind written by Jack Finney and Charles Beaumont, and the sword-and-sorcery tales of Fritz Leiber, Lin Carter, and Karl Edward Wagner. These days, the term dark fantasy means an entirely different thing to many people.

What’s the lesson learned? Never judge a story by the genre label.

There’s another lesson here too.

Despite my limited track record in writing introductions to the works of other writers, I must admit that penning one for a relatively unknown, new writer came with a sense of caution.

So far, I’ve managed to escape similar solicitations from other writers. On the rare occasions I am asked, I turn them down for one simple reason: my downtime is limited, and what I choose to read in that off time is usually very discriminating. I tend to read for pleasure and entertainment, and having spent far too many years of self-flagellation (as a fiction editor for two horror magazines and as coeditor of an anthology), I’ve read far too many stories by beginning writers. I didn’t want to inflict the same kind of torture on myself at this stage of my career. Sure, the works of newer writers appearing from the various small presses these days are vetted by the men and women behind their respective ventures, but editorial tastes vary. How could I trust that the editorial tastes of publisher/editor A would strike my fancy? It’s a crapshoot. Back in the Cenozoic Period (that is, 1980s and most of the 1990s), I used to sample everything the small press had to offer. I felt I had to stay on top of things in the field in order to be current.

If anything, this gave me cancer of the eyeballs.

Works that were hyped endlessly with blurbs and glowing introductions turned out to be not so hot.

The passing of time has only proved me right, as much of the material I read with wide-eyed enthusiasm back then has been not only forgotten by me, but has remained forgotten in the minds of many readers. The writers themselves have disappeared.

I suspect Fairy will not receive the same treatment. Two months after first reading it, I still can’t get it out of my mind.

It’s obvious I made an exception to my “No Introductions for Other Writers” policy with Shane McKenzie since, well…here I am, introducing the work of a new writer most of you have probably never heard of. Because it is my policy, I reserve the right to change it whenever I goddamn well feel like it.

I’m glad I did in this case. Here’s why:

Shane McKenzie has done what every beginning writer should do with the novella format—make the reader feel something. In the field of horror, that something should be an underlying sense of dread, of fear, of unease. I felt all of that while reading Fairy, but I also felt something else:

Empathy.

The main character in Fairy, Cecilia, is a single woman who works as a doula (a nonmedical person who assists women before, during and after childbirth) under the direction of Judy, who owns a company that assists in live births performed in the private home of the patient. Cecilia wants a child of her own and has been undergoing fertility treatments due to her inability to conceive. Shane McKenzie does a splendid job of creating Cecilia’s backstory so perfectly that you can’t help but immediately connect with her.

Of course, a reader must empathize with characters somewhat. Not necessarily identify with them, but they should feel some kind of connection. They must be believable. The reader doesn’t necessarily have to like them, but the character must be three-dimensional in every way. Shane accomplishes that with Cecilia’s character, and he does it with Judy too. He accomplishes this feat even more admirably with Cecilia’s conflict—her infertility problem.

I imagine this will strike home with those readers who have undergone similar issues.

And even for those who haven’t gone through similar problems, or who have never desired children, I suspect you will still feel for Cecilia.

That’s how powerful a writer Shane McKenzie is.

To comment further on this novella—specifically, even hinting at the events that unfold that lead to the fairy in the story—would be to spoil it. And I can’t do that. You will just have to trust me on this. What I can reveal is that Shane McKenzie has developed a completely unique creature in Fairy, one that I’ve never come across in the field of dark fiction/horror. While Fairy falls squarely in the be-careful-what-you-wish-for subgenre, it is not a simple deal-with-the-devil story, much less a deal-with-anything kind of yarn. There are no Judeo-Christian demons or devils

in Fairy. Instead, Shane McKenzie has created a creature from the old myth of fairies and taken it back to its medieval roots.

You see, fairies aren’t beings of light that fly around granting our every wish.

The fairy legend can be found in multiple cultures and they have many origins. One belief is that they were the dead, or a subclass of the dead. Another view holds they are an intelligent species, distinct from humans and angels. Yet another belief is they are a class of demoted angels. Only in modern times have they been depicted as young, winged, humanlike in stature.

What most of the old stories of fairies have in common is the fairies’ malevolence: there are charms to keep them away from babies (which they are known to steal), from the elderly. They can be mischievous. Cunning. Harmful.

And they can bite.

As a novella, Fairy has plenty of bite. It is visceral in places, both physically and emotionally. It isn’t enough to depict visceral bloody scenes in fiction—there has to be an emotional element too. Too many beginning writers go straight for the gross-out or the extreme when the story doesn’t call for it. And while Fairy isn’t nearly as intense on a visceral level as some of Edward Lee’s material (a writer McKenzie obviously greatly admires), it can certainly be classified as visceral or extreme. It strikes a careful balance between the depiction of graphic violence and narrative. It doesn’t go too far because it doesn’t have to. Yet at the same time, I suspect some readers will find some scenes in Fairy to be too much, that they’ll read this thinking, “Oh my God, what the hell did he just do here?”

And you know what? If you think that and you keep reading anyway, then Shane McKenzie has done his job.

Shane McKenzie has a bright future. He has a lot of years ahead of him. Fairy represents a stepping stone of sorts, the beginning of what will be more stories and, hopefully, novel-length works.

He’s off to a good start.

Enjoy the following story. And remember…

…be careful what you wish for.

You just might get it.

J. F. Gonzalez

Lititz, PA

June 13, 2012

Fairy

“I can’t…please, I c-can’t do it…”

“Yes you can,” Cecilia said. The woman’s grip tightened, and Cecilia ignored the pain of her knuckles grinding together. “Now push, you’re almost there, push!”

“Oh shit, baby…I can see it, I-I can see the head.” The man peered into his wife’s birth canal as the doctor sitting between her legs smeared some more oil over the opening. The father’s smile sizzled into a frown.

Cecilia smiled into the woman’s face, brushed the hair away from her sweaty forehead. The woman bared her teeth, clenched them, squeezed her eyes shut. Her toes turned white as she scrunched them on the metal stirrups, and every vein on her face and neck bulged as another surge erupted in her body.

“Oh god…oh fuck, please…please take it out of me, you gotta take it out.” She searched for her husband with wild eyes, the man pacing the room, shaking his hands at his sides and taking deep breaths.

“Focus,” Cecilia said. The woman squeezed her hand, and Cecilia squeezed back. “Home stretch, okay? You got this, you can do it.”

The woman turned to her, gave her a look that said, Why don’t you go fuck yourself?

But this was something Cecilia was used to as a doula. At the rate of at least one birth per week, she’d been called just about every cussword in the book.

“Come on, a big, strong push,” the doctor said, her eyes never leaving the widening vagina. “For your baby, another big push.”

“Ahhhh!”

“Keep going, here she comes.”

No matter how many births Cecilia had witnessed, no matter how many new babies she’d seen enter the world, she would never get used to that first wail. As the doctor set the bellowing newborn into its mother’s arms, warm tears spilled down Cecilia’s face, and she had to turn away from the mother and child to collect herself.

“Oh my god…oh thank you, thank you so much,” the woman said over the cries of her daughter.

The father had calmed himself, had shaken hands with the doctor and now stood beside his family, exchanging kisses with his wife and choking back sobs.

“Congratulations, you two,” the doctor said. “She’s beautiful, and you did great.” And then she quickly spoke to the nurses and walked out the door, surely on to the next birth.

Cecilia wiped her face, took a long, deep breath and turned back toward the family. The woman was already looking at her, smiling. “Thank you,” she said. “I don’t know what we would have done without you, thank you.”

“You did amazing, sweetie. Amazing.” Cecilia leaned over and studied the child. Pink and wrinkly and glistening, the tiny girl gurgled as she cried, thrashing her little limbs.

And another wave of longing struck Cecilia in the gut; she again had to turn her face away from the happy couple, hold her breath to try and suffocate the sobs before they came.

“You all right?” the woman said.

Jesus Christ, this woman just gave birth, and you’re such a fucking mess that she has to ask if you’re all right?

Cecilia forced a smile, turned back to the woman. “Oh please, don’t worry about me. It’s the happiest day of your life.” She stood, gave a slight nod, then quickly exited the hospital room. It wasn’t until she stumbled into the hallway that she realized how thick the air was in the room, and she took lungfuls of cool oxygen as she slid down the wall and collapsed to her backside.

The birth had lasted twenty hours, and as the doula, Cecilia had to stay for the whole thing, support the woman, massage her, talk her through it. The fatigue took hold of her like the fist of a giant, and she rubbed the heels of her palms over her eyes.

The muffled cry of the new baby girl blasted from inside of the room, and Cecilia’s hand went to her own stomach, clawed at it, pinched the skin through her shirt. A big chunk of her hated this woman, hated her for having the ability to bear a child, hated her for having a husband who stands by her side and loves her.

Then she shook her head and laughed at herself. Tired, she thought. I’m just tired. She rose to her feet, winced at the ache in her back, stepped back into the room.

It looked as if the baby had been cleaned up, umbilical cord cut, and was now at her mother’s breast, unsure of what to do as its toothless maw gummed at the brown nipple.

“I think I’m going to head home, get some sleep,” Cecilia said to the couple. “You guys are parents now. How does it feel?”

“It feels incredible,” the woman said. She smiled. “Thank you so much again. We’ll definitely be referring you to our friends and family.”

The father chuckled. “Without you here, I think I may have jumped out of the window.”

“Well, you two enjoy your baby. The office will call you tomorrow just to check in.” They all exchanged a few more smiles, a few more thank-yous, and then Cecilia was in her Camry, forehead rested on the steering wheel, sobbing and letting the tears and mucus puddle on the vinyl of her seat between her legs.

She forced herself to start the car, and was all at once blasted with fetid air from the vents and Aerosmith from the speakers. A laugh escaped her lips as she turned the volume knob, cut off the air conditioner and rolled her window down. The smell of the night air helped calm her nerves, and she pulled away from her lonely parking spot and headed toward the highway.

The music calmed her, and she managed to make it all the way to her driveway without another flood of tears. When she’d first started as a doula, it was almost therapeutic for her. Every birth she attended was a miracle, full of joy and happiness, both for the new parents and her. She could live vicariously through them.

But after…everything happened, she began to resent these people. Seethe with jealousy as she watched each he

althy child slide out of its mother’s womb, take its first breath of air, latch on to its mother’s breast.

I love my work, she told herself. I love what I do.

“Then what’s your fucking problem?”

As she slid her house key into the lock, she could already hear Skittles bouncing with excitement. She smiled and shoved the door inward, and was nearly knocked off her feet by the Great Dane as it leapt into her arms, bathed her cheeks and neck with tongue juice.

“Hey, my sweet baby.” She scratched behind the dog’s ear, got its hind leg kicking and scraping the floor. “You’re such a good girl. Mama loves you.”

Her body begged her to lie down, to let sleep beat her into submission, but she found herself pouring a glass of wine instead. She sat at her kitchen table, stared at the placemat with zoned-out vision, lost in her own scattered thoughts. Skittles laid her oversized head in Cecilia’s lap.

The wine tasted bitter, but Cecilia gulped it down anyway. She prodded the gold wedding ring on her left hand, spun it over her finger. Without her consent, her eyes darted across the room to the framed photo of her and Frank, freshly married, Frank hugging her from behind, Cecilia’s wedding dress flowing about her. Both smiling like idiots at the camera, smitten with each other, intoxicated with love.

She scratched Skittles between the eyes, shuffled across the kitchen, poured the rest of her wine down the sink drain and headed for her bedroom.

Cecilia closed her eyes as the doctor fed the catheter past her cervix and into her uterus, expelling the concentrated sperm into her like cream filling. Though she was ovulating, she didn’t expect anything to happen, knew her egg wouldn’t take the sperm.

But a tiny voice in the back of her mind still held hope. Told her to be optimistic, that miracles happen every day, that women who are told they can’t have children prove doctors wrong all the time.

Her fist balled up and tore the paper beneath her as a needle of pain rode her flesh. She kept her eyes closed, her head turned so the doctor couldn’t see the hopelessness on her face.

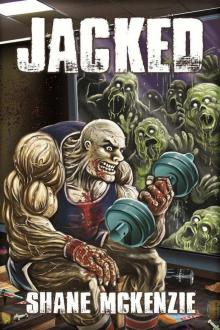

Jacked

Jacked 2013: The Aftermath

2013: The Aftermath Parasite Deep

Parasite Deep Ruthless: An Extreme Shock Horror Collection

Ruthless: An Extreme Shock Horror Collection Fairy

Fairy The Bingo Hall

The Bingo Hall Infinity House

Infinity House Addicted to the Dead

Addicted to the Dead Pus Junkies

Pus Junkies Stork

Stork